Black Madonna

Essay

“She went quickly to Rocamadour saying ‘This is the doing of the Virgin who always guards us.’”

(From a Medieval pilgrimage song)

In the mid 90’s I experienced an identity crisis as an artist. I wanted to find a spiritual connection that could be manifested in my work and realized that I was connected in a way that had been with me all along. I began to reflect on my family’s Slavic heritage. When I was growing up a woman’s eyes were always watching me from a picture on the wall of my grandmother’s kitchen. It was a picture of the Black Madonna of Czestachowa. (Fig. 1)

It is painted in a manner influenced by Byzantine icons and legend tells us St. Luke painted it on the wood of the table of the Holy Family. Her face is dark and stern. Not sweet like other Madonna images I’d seen. It was made more imposing by two scars across her right cheek cut by Hussites when they attacked the Pauline monastery in which the Madonna is enshrined.

She is the Madonna of the Jasna Gora monastery in Czestachowa, a small city in southern Poland. Her image and what it represents became a muse and spiritual guide for me influencing my work for several years. During that time I sometimes employed her image but it was largely the metaphor conveyed by it into my work that was of greater importance. I found that the Black Madonna represents the need to encounter what Master Eckhart called the ground of the soul that is dark in order to attain inner peace and an authentic connection to the spiritual that will allow for transformation to a new creative consciousness.

Jung’s concept of the anima and animus is significant. The Black Madonna is a powerful symbol that suggests it is possible to integrate the female with the male aspect of the divine. All of us have within us both feminine and masculine realities. To disregard one in favor of the other is to deny wholeness of the psyche. A “creative urge in man is rooted (in the) Black Mother. She is both the source of a new consciousness and the well spring of all creativity.”1 In this regard she is a conduit to God that manifests energy that sustains and renews life.

I became further involved with the mystery of the Czestachowa Black Madonna in 2004 when I was awarded a Fulbright teaching and research fellowship. The project was called “Black Madonna Query.” The title reflected my desire to understand the phenomenon of the Czestachowa Madonna more deeply.

I began creating subtle references to her mythic aspects. For example “She Remains” (Fig. 2) shows a row of coral necklaces, ex-votos in the Czestachowa shrine, one with a bead on which I placed the visage of the Black Madonna.

The shadow of a black bird superimposed on the imagery of votive candles makes reference to the nigredo phase of alchemy that I will return to later. The coral necklaces resemble rows of corn and thus the title refers to the Great Mother Goddess as the original grain guardian with a lineage that traversed the centuries.

During my Fulbright experience I made a series of paintings, drawings and digital photographs and continued the work when I returned. In my explorations I found that there is a surprisingly large

number of Black Madonnas, many located in obscure country churches as well as major pilgrimage sites in southern and south central France. My goal to walk the paths of Medieval pilgrims was realized when I received a University of Nebraska research grant for the summer of 2008.

I visited five major Black Madonna Shrines in France; Notre Dame of Rocamadour, Notre Dame de Confession in Marseilles, Notre Dame du Puy of Le Puy-en-Velay, Notre Dame de Bon Espoir in Dijon and Notre Dame du Pillier in Chartres.

The Black Madonnas of France

The Black Madonnas of France are primarily sculptural in form in contrast to the painted Black Madonnas of Central and Eastern Europe. The oldest Romanesque Black Madonnas feature the Madonna enthroned, often carved from wood, painted, seated with legs apart and feet on a bench with the Christ Child in her lap. 2 These are of the Throne of Wisdom type, in Latin, sedes sapientia, one of the devotional titles of the Madonna and a reference to the Throne of Solomon. In the Book of Solomon Wisdom is depicted as feminine. “Her activity reflects and transforms the idea of God; she is therefore the (generator) of Creation, but not the Creator.” 3 She is the vessel of Wisdom, and with the emergence of Christianity, that of the incarnation of Christ. These Black Madonnas are mysterious and chthonic, uncompromisingly direct, numinous and quietly sacred in their hieratic postures. “Peculiar to all the Romanesque (Throne of Wisdom Madonnas, both white and black) is the look of an idol, albeit a “Christian idol” 4 An interpretation is that the Black Throne of Wisdom Madonnas are depicted as such because the color black represents the primal and creative, the matter out of which all things come. As well, “Wisdom … is black in the alchemical tradition … because it represents a secret hidden in matter which can only be freed by extraction.” 5

The origin of the phenomenon of the Black Madonna is unknowable but there are several theories as to how it emerged. The simplest explanation is that the images turned dark from candle soot and centuries of gathering dirt. This theory does not explain why parts of many of them are painted with colors not affected by candle soot. Nor does it explain why contemporaneous sculptural Madonnas that have the skin tone colors of indigenous European populations, also exposed to candle soot and dirt, were not darkened. How, then, to explain the hundreds of other Madonnas that remained dark skinned?

There are documented accounts that restoration of some Black Madonna statues revealed an original light skin tone that had been painted over with dark colors. One such is the Madonna of Einseindeln in Switzerland. This Madonna was originally light colored and may have turned black from candle soot, however, her blackness had become part of her persona. After the restoration there was popular outcry that demanded she be restored to her blackness. 6

Another theory is that Mary was from the Middle East and would naturally have had dark skin. Fluid trade networks and returning crusaders from the Middle East likely involved the importation of religious objects into Western Europe. 7

There is yet another theory that is supported by several important Black Madonna scholars. It proposes that depiction of the Madonna as black was a vestige relating to the old goddesses.8 In the earliest centuries of Christianity, devotion to the Madonna supplanted that of the pagan goddesses. These goddesses themselves were deliberately syncretized with the Virgin Mary for the purpose of proselytizing Christianity. Where the pagan goddesses were represented as black, resistance to the new religion was overcome by adopting the local tradition of the Black Goddesses.

The Egyptian goddess Isis as wife of Osiris and mother of Horus, is at the primary mythic and archetypal core Mother, Son and Consort. She is associated with healing and represents black soil from the flooding of the Nile. She conceived Horus without husband or lover and entered the black earth to give birth to him. 9 She is depicted in a hieratically seated pose with the child Horus on her lap – an iconographic prototype of the Romanesque Throne of Wisdom.

Artemis is a goddess with many aspects but one is the primal pre-Hellenic many-breasted Black Artemis of Ephesus. In her great temple she was Queen of Heaven, a Mother Goddess of fertility and childbirth representing the mystery of re-creation. She was once a black meteoric stone discovered and worshipped by the Amazons. 10 Ephesus was the city from which St. Paul preached and discouraged the worship of idols. 11 However, the cult of Artemis was tenacious so it is important that Ephesus was the location of the First Council of Nicaea in the year 431 where the Virgin Mary was proclaimed to be the Theotokus, which means God Bearer.

Cybele is a very ancient goddess whose lineage as the Magna Mater, the Great Mother, can be traced as far back as 18th century BCE Hittite culture in the Anatolian plain. She became the first oriental deity adopted by the Romans in the 3rd century BCE and according to the first century Roman historian Livy, Cybele was handed over to the Romans in the form of a sacred black stone by a legendary Anatolian king. 12

Fertile earth is black – and this blackness is likely a key factor contributing to the dark avatars of some of the ancient Goddesses. By the 12th century the Madonna that had taken over from the old grain goddesses responsibility for the sustenance and nourishment of humankind. 13 “The color black … was in Old (archaic) Europe the color of … the soil. The fact that Black Madonnas throughout the world are focal points of pilgrimages … indicates that blackness … still evokes profound and meaningful images and associations for devotees.” 14

Perhaps the most important theory, and most relevant to my work and interest in the Black Madonna, is that she represents an archetype, “an inward image at work in the human psyche” 15 It is also, according to Jung, a fundamental pattern consisting of primordial images that all human beings are born with and are capable of accessing. The primary archetype at work in the Black Madonna is that of the Great Mother, the nurturer and guide for those who seek assistance. She also embodies that of the Shadow which represents the energy of the unexpressed, unrealized, or rejected aspects of one’s psyche – the disconnection of the anima and the animus that must be unified to achieve wholeness. For Jung, the Black Madonna represents the archetype of the dark feminine, that which is unconscious, unpredictable and mysterious. “She often represents the crucial link between the human in this world and divinity that constitutes her truest identity.” 16

In alchemy the nigredo, or black is the first state in the transmutation of base metals into gold. Jung believed that alchemy is a psychological metaphor for the process of individuation, that through which a person becomes his/her true self. Black represents the death of the false self. “Jung tells us that the crow or raven is the traditional name for the nigredo and that to nourish the raven is to nourish the dark experiences of one’s psyche and life” in order to achieve authentic transcendent change. 17

The Black Madonna Shrines

Many of the Black Madonnas are associated with the presence of a spring or sacred fountain. “Water is … understood as a mother symbol and Jung believed that the projection of the mother image onto water endows it with numinous or magical qualities. 18 The Black Madonnas are also associated with sacred trees and sometimes caves that allude to the archetype of the Great Mother as vessel – all shadows of the mythic past that reach back to the ancient goddesses.

In the Middle Ages there was a surge of cults to the Madonna. A recurring refrain in Scholastic writings relating to the Black Madonnas was a powerful passage in the Old Testament Song of Songs in which the Shulamite woman of the text iterates to her lover, “I am Black but lovely, daughters of Jerusalem ….Take no notice of my dark colouring.” 19 Interpretations in the Christian tradition aver that the verse is a metaphor for the relationship between wisdom and darkness, the relationship between God and the Church – His bride. “Here we meet Wisdom as the Bride of the sacred marriage.” 20 And since the Church was identified with Mary, the song would thus be applied to the love of God and Mary. 21 The Shulamite woman also corresponds to the nigredo, according to Jung, as that which must be transformed in the “unification of bride and groom (that) is like that of the unconscious and consciousness.” 22

Rocamadour

The shrine of Our Lady of Rocamadour (Fig. 3) is located on a site that is thought to have been the center of the cult of the Roman goddess Cybele. 23

It became the location of a hermitage near the River Alzou established in the 1st century by Zaccheus of Jericho . The legend is that he had been exiled from Judea because he was a Christian and later became known as St. Amadour. His practice was to venerate a statue of the Virgin was carved by St. Luke and carried by Zaccheus /Amadour to the site. In the 12th century when an oratory was to be built, the body of St. Amadour was found completely intact and reburied at the entrance.

The small town of Rocamadour hangs off the side of a cliff in the Dordogne region of southwestern France. In the Holy City one encounters the Romanesque Basilica of St. Sauveur that has a series of 7 small sanctuaries. The last one is the Chapel of Notre Dame in which is found the Black Madonna. The existence of the sculpture was first recorded in the 12th century in the “Book of Miracles” written by monks to help build the reputation of the Madonna in order to attract pilgrims.

This was the first Black Madonna shrine I visited on my pilgrimage and moving through the chapels to reach her shrine did not prepare me for the experience of the encounter with her. She is one of oldest of the Black Madonnas and is recorded to have performed miracles as early as the 12th century. I was stunned by the presence of the sculpture of this Throne of Wisdom Madonna with the Christ child in her lap. Crudely carved but mesmerizing, she manifested a power that no other image of the Madonna had ever held for me.

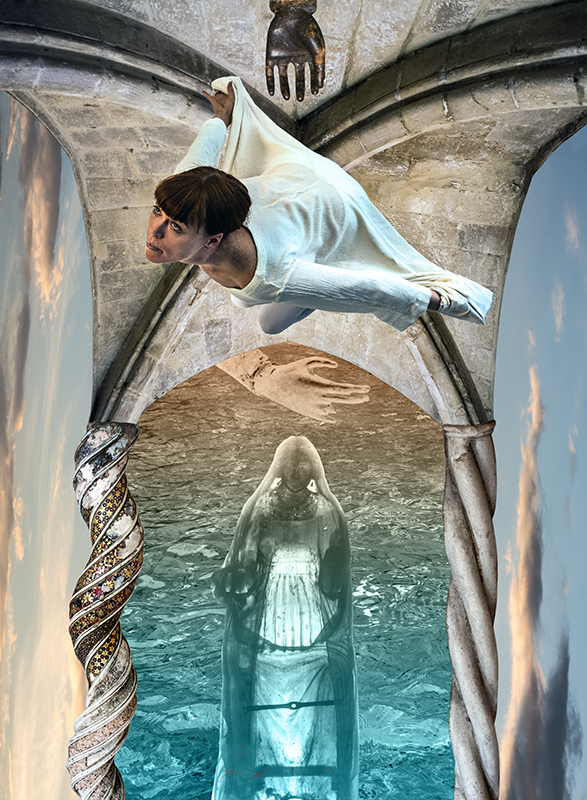

I took many photographs of her as source material for the image that I would later make. The piece I created, (Fig. 4) includes only her head placed below a Romanesque vault from a photo I took in the Dordogne region around Rocamadour.

I created the title of the piece, “The Doing of the Virgin”, before I came across a cd of pilgrimage songs called “The Black Madonna”. 24 Reading the song lyrics I was surprised to find a phrase in one of them, ‘This is the doing of the Virgin who always guards us” in specific reference to the Black Madonna of Rocamadour. This was a mysterious and startling moment in my explorations.

Marseilles

The Notre Dame de Confession (Fig. 5) is located in the crypt of the Romanesque Basilica of St. Victor near the port of Marseilles.

Legend has it that the cult of the virgin in Marseilles has existed since the end of the second century and asserts that the statue was sculpted from walnut by St. Luke, and brought to Marseilles by Lazarus. 25 More than likely the original was made in the 13th century and the current polychromed statue is a 15th century copy. 26 The pose of the virgin is again iconographically that of the Throne of Wisdom.

The crypt is cavernous and spacious, filled with sarcophagi, sculptures, frescoes and includes an unusual relief sculpture of Mary Magdalene carved out of the living rock of the crypt, belly large, seeming to be pregnant.

On descending to the crypt I was confronted with a golden atmosphere, the lighting reflecting off the warm colored stone. The small room in which the Black Madonna of Confession resides is not totally enclosed so she can be viewed from other points of view in the crypt. She is placed in a corner and from outside her space a certain ¾ view of her is severely cropped and this was the primary image I used for my piece, “Confession” (Fig. 6).

There is another image of her to the lower left that was photographed frontally and in the work, rendered in a blurred manner as if under water. At the bottom of the vaulted dome above her stands a raven.

Le Puy en Velay

Le Puy en Veley located in the Auvergne region in the Massif Central of south central France is built in a valley among numerous volcanic formations. With Chartres, it is the oldest Marian shrine in France going back to the 1st century. The heavily restored Romanesque Cathedral, Notre Dame du Puy, is thought to have been built on the site of the Roman temple of Diana. 27 The Roman temple itself was built on a major Druidic center of the cult of the Goddess Annis, the Celtic parallel to Diana, the Roman equivalent of Artemis.

According to tradition the original statue of the Black Madonna was transported to Le Puy in the 13th century from the Middle East by St. Louis upon his return from the 7th Crusade. A statue that may have been this Black Madonna was burnt during the French Revolution with cries of “down with the Egyptian.” Detailed drawings of it were made by the architect Faujas de Saint-Fons in the late 18th century and from these a replica of the Romanesque Madonna was made in the early 19th century. The Madonna is another of the Throne of Wisdom type. (Fig. 7) The replica is currently in the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament on the north side of the Cathedral.

There is a second statue of a Black Madonna, from the 17th century, that has been positioned high above the altar since 1844 and it is this statue (Fig. 8) that is processed on feast days.

The piece I made, “Two Madonnas”, (Fig. 9) about the Le Puy Black Madonnas once again depicts a Romanesque vault.

It features the mirrored head of the more recent Black Madonna with the more ancient one in smaller scale at the base of the vault. At the very bottom of the piece is a strip of evening sky with a crescent moon – an ancient symbol of both Isis and Artemis. I designed the piece around the idea of the eternal wisdom of the Black Madonna and the light that can be reached if one will journey through the metaphorical and spiritual nigredo that she represents.

Dijon

Dated from the 11th to 12th centuries the Romanesque Notre Dame de Bon Espoir, Our Lady of Good Hope of Dijon, (Fig. 10 ) is one of the oldest statues of the Madonna in France and is found in the 13th century Church of Notre Dame of Dijon in the Burgundy region of Eastern France.

This Throne of Wisdom Madonna was also desecrated during the French Revolution. The Christ Child was removed from the shelf on the lap between her outspread legs and her hands and feet are cut off. Yet her iconic power is not diminished. Unlike the other Black Madonnas I saw, she is just under life size, with a long narrow head, thin nose, her head very slightly turned to her right. With her gaze looking downward her face has a vulnerable appearance. Contributing to this effect are her pendulous breasts and large, protruding belly, features that were not part of any of the Black Madonnas I saw on my pilgrimage or in reproductions. In Jungian psychology the belly symbolizes the elementary and totality of the body-vessel – it is the symbol of the womb of the earth. 28

A 1945 restoration showed that the Notre Dame de Bon Espoir was not originally black and had a lighter, though not white, visage. Before the restoration the face was painted black and the clothing of the Virgin was entirely covered with a ruddy brown color with gold trim on the garment, perhaps following the example of the Madonna of Le Puy and of that of Chartres in order to compete with their cults. Interestingly, after the restoration, the statue continued to maintain its reputation as a Black Madonna out of respect for local tradition. 29

The piece titled “Bon Espoir” (Fig. 11) that I made for the Madonna of Bon Espoir depicts a groined vault making 6 radiating triangular shaped spaces.

The Madonna’s translucent figure is in the lowest. In the upper left there is a view of the clerestory of the Archaeology Museum of Dijon. The upper right depicts a female demon on her knees from a photo taken of a fresco in the north chapel. The upper triangle has an image of a reliquary with a face placed where a saint’s relic would be that symbolizes wisdom. The imagery of the vaults and fresco reference the structure and imagery of the Gothic cathedral, and the demon is a metaphor for the darkness of the nigredo phase of alchemy.

Chartres

The late 15th century statue Notre-Dame du Pillier, Madonna of the Pillar, (Fig. 12) is found in the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres.

The statue is found in the first bay of the north side of the ambulatory and was erected toward the end of the 15th century. 30 The sculpture is situated atop a pillar and was carved from either walnut or pear tree wood. The Madonna is seated with the Christ child on her left knee. The statue’s origin is not known for certain though there is documentation that it may have been donated by a canon in 1220 emulating an older Black Madonna. 31 More than likely, however, it was made during the Renaissance.

I entered the ambulatory from the south transept and at the end of the journey to the north end I encountered the golden atmosphere of the chapel. Many candles offered by pilgrims softly illuminated the space creating a warm and mystical effect, The statue on the pillar is set into the ribbed half dome niche that is filled with ex votos of hearts of gold – offerings for answers to prayers through the intercessions of the Black Madonna.

There is another, older Black Madonna associated with Chartres, La Vierge de Sous-Terre, Our Lady of the Underground, that was originally located in the crypt but disappeared during the French Revolution and later replaced with a replica. In the crypt also is the Puits des Saints Forts, Well of the Powerful Saints, derived from the name “Locus Fortis”, “the Strong Place” and is located beneath the nave of the cathedral. Tradition tells us Our Lady of the Underground had always been sited in close proximity to this well, associating her with water imagery.

“The sanctuary of Chartres was built on ground held sacred since earliest antiquity. 31 It is known through the writings of Julius Caesar and Pliny that this site had been a Druidic center where annual meetings took place in clearings and consecrated spaces. Some of their deities would also have been venerated in caves and grottoes near springs or wells. 32 The Druids were known to have worshiped a fertility goddess known as the ‘Virgin on the point of giving birth’. This phrase in Latin is ‘Virgini Pariturae’ and it was inscribed at the base of a statue likely of Gallo-Roman origin. 33 The imagery of the “Virgini Pariturae” was adopted in sculptural form in the Christian era. Documentation of the statue’s appearance in the late 17th century describes in detail an image of the Throne of Wisdom type. Verifying this is a drawing signed ‘Leroux’ and on top of it is a banner on which is written the text “Virgini Paritura. 34

In the piece I made as homage to the Black Madonna of the Pillar and the Madonna-Sous-Terre which I titled “Fountain”, (Fig. 13) I focused on water and rock imagery.

This was to reference the Druidic custom of revering their goddesses near water sources as well as caves. The face of the Madonna of the Pillar is placed, as if under water, at the bottom of the piece and hovering above her is a rock surface in which is embedded a number of images. They include one of the standing saints from the West entrance of the Cathedral, a Romanesque carved face, a reliquary object, and the image of a labyrinth. To the right, I once again reference the nigredo phase of alchemy with two small ravens transparently placed over the water.

In making my images I did not begin with an idea of what a final piece would look like. For each I began simply with an image of the Black Madonna and searched through many other photographs from my pilgrimage. I wanted imagery to set a metaphorical context based on the spaces that I felt, remembered and imagined from visiting the shrines. The painstaking process I employed in making the pieces was a subconscious one, trusting myself to access through visualization the archetypes I believe are present in the Black Madonna.

The tradition of pilgrimage has been a part of human activity for thousands of years. The emergence of Christianity sustained these practices from its perspective over the centuries and devotion to the Black Madonna has been significant. There was great interest in the phenomenon of the Black Madonna during the last century and an impressive resurgence in the past several decades. Pilgrims go for many reasons. For me it was necessary to make this journey as an artist. After the pilgrimage it took a while for the experiences to rest inside of me. I struggled with the challenge to synthesize my personal and visual experiences to create images that could express and represent them. I went through my own dark night of the soul in the process of creating the body of work. I am still not finished. This was not a project that had a clear beginning nor does it have a clear end.

Footnotes

1. Fred Gustafson, The Black Madonna (Boston: Sigo Press, 1990), 51.

2. Marie Durand-Lefebvre, Etude sur l’origine des Vierges Noires (Paris: Durassie & Cie Imprimeurs, 1937), 50.

3. Caitlin Matthews, Sophia: Goddess of Wisdom, Bride of Christ (Wheaton, IL: Quest Books-Theosophical Publications, 2001), 97.

4. Ilene H. Forsyth, The Throne of Wisdom (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 9.

5. Rosemary Murray, Jung, Black Madonnas, and the Priority of the Maternal (MA thesis, Carleton University, 2000), p66.

6. Fred Gustafson, The Black Madonna (Boston: Sigo Press, 1990), 40.

7. Marie Durand-Lefebvre, Etude sur l’origine des Vierges Noires (Paris, Durassie & Cie Imprimeurs, 1937), 129 and 137).

8. Ibid, 150 to158.

9. Raymond LeMieux, The Black Madonnas of France (Carlton Press, Inc., 1991), 19.

10. Ean Begg, The Cult of the Black Virgin ( London and New York: Arkana, 1985), 18 and 57.

11. Acts of the Apostles 19:23-28.

12. Carl Olson editor, The Book of the Goddess, Past and Present, M. Renee Salzman, “Magna Mater: Great Mother of The Roman Empire” (New York: Crossroad, 1989), 62.

13. Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (London: Arkana, 1991) 576-577.

14. Maria Gimbutus, The Language of the Goddess (San Francisco: Harper, 1989), 144.

15. Erich Neuman, The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), p. 3.

16. Carl Olson editor, The Book of the Goddess, Past and Present, Pheme Perkins, “Sophia and the Mother-Father: The Gnostic Goddess (New York: Crossroad, 1989), 107.

17. Fred Gustafson, The Black Madonna (Boston: Sigo Press, 1990), 13.

18. Rosemary Murray, Jung,Black Madonnas and the Priority of the Maternal (MA Thesis, Carleton University, 2000, 14-15.

19. Song of Songs 1:5 (The New Jerusalem Bible).

20. Caitlin Matthews, Sophia: Goddess of Wisdom, Bride of Christ (Wheaton, IL: Quest

Books-Theosophical Publications, 2001), 35.

21. Stephen Benko, The Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Pagan and Christian Roots of

Mariology, (Leiden – Boston: 2004), 213.

22. Fred Gustafson, The Black Madonna (Boston: Sigo Press, 1990), 10.

23. Ean Begg, The Cult of the Black Virgin ( London and New York: Arkana, 1985), 79.

24. CD, Black Madonna Naxos, Ensemble Unicorn, Track 3.

25. Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, Vierges Noires (Editions du Rouergue), 69.

26. Ibid. p. 24.

27. Anneli S. Rufus and Kristan Lawson, Goddess Sites Europe (San Francisco: Harper, 1990) 53.

28. Erich Neuman, The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 44.

29. Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, Vierges Noires (Editions du Rouergue), 96 to 99.

30. Jean Markale, The Great Goddess (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1997). 139.

31. Jean Markale, Cathedral of the Black Madonna: The Druids and Mysteries of Chartres (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1988) 169.

32. Jean Markale, The Great Goddess (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1997), 139-140.

33. Marie Durand-Lefebvre, Etude sur l’origine des Vierges Noires (Paris, Durassie & Cie Imprimeurs, 1937), 156.

34. Jean Markale, Cathedral of the Black Madonna: The Druids and Mysteries of Chartres (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1988) 260-261.

39. Ibid, 260-261.

40. Jean Markale, The Great Goddess (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1997). 139.

41. Jean Markale, Cathedral of the Black Madonna: The Druids and Mysteries of Chartres (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1997). 169.